being the only speech that is natural to Man… may well be called the Tongue and General language of Human Nature, which, without teaching, men in all regions of the habitable world doe at the first sight most easily understand.

The overarching aim of this work, however, was made clear by his second book, which explicitly dealt with the education of the deaf:

Philicophus bears a remarkable frontispiece illustration which appears to show a deaf man conducting music from a cello viola de gamba* through his teeth.

* Thank you to Warren Stewart for this correction.

Next Bulwer published Pathomyatomia, one of the first works to study the action of the muscles of the face in producing expressions (presaging the rather gruesome electrical experiments of nineteenth century French neurologist Duchenne de Buologne).

Bulwer’s final published work features what may be my favorite book title of all time: Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d, or the Artificial Changeling. Historically presented, in the mad and cruel Gallantry, foolish Bravery, ridiculous Beauty, filthy Fineness, and loathesome Loveliness of most Nations, fashioning & altering their Bodies from the Mould intended by Nature. With a Vindication of the Regular Beauty and Honesty of Nature, and an Appendix of the Pedigree of the English Gallant. (London: J. Hardesty, 1650). This fascinating book is something I’ll write about at a later date [April 2012 update: see here] since I suspect it will find its way into my dissertation research. For now, I present an image from it which indicates something of the book’s bizarre character:

Finally, a note on the Iberian origin of much of Bulwer’s work, and of the study of deafness and gesture in seventeenth century Europe more generally. The work of Juan Pablo Bonet (1573-1633), an Aragonese priest and writer of the Spanish Golden Age, predated Bulwer’s writings by some forty years, and probably marks the first efforts to educate the deaf to appear in print.

|

| Juan Pablo Bonet’s Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (1620). |

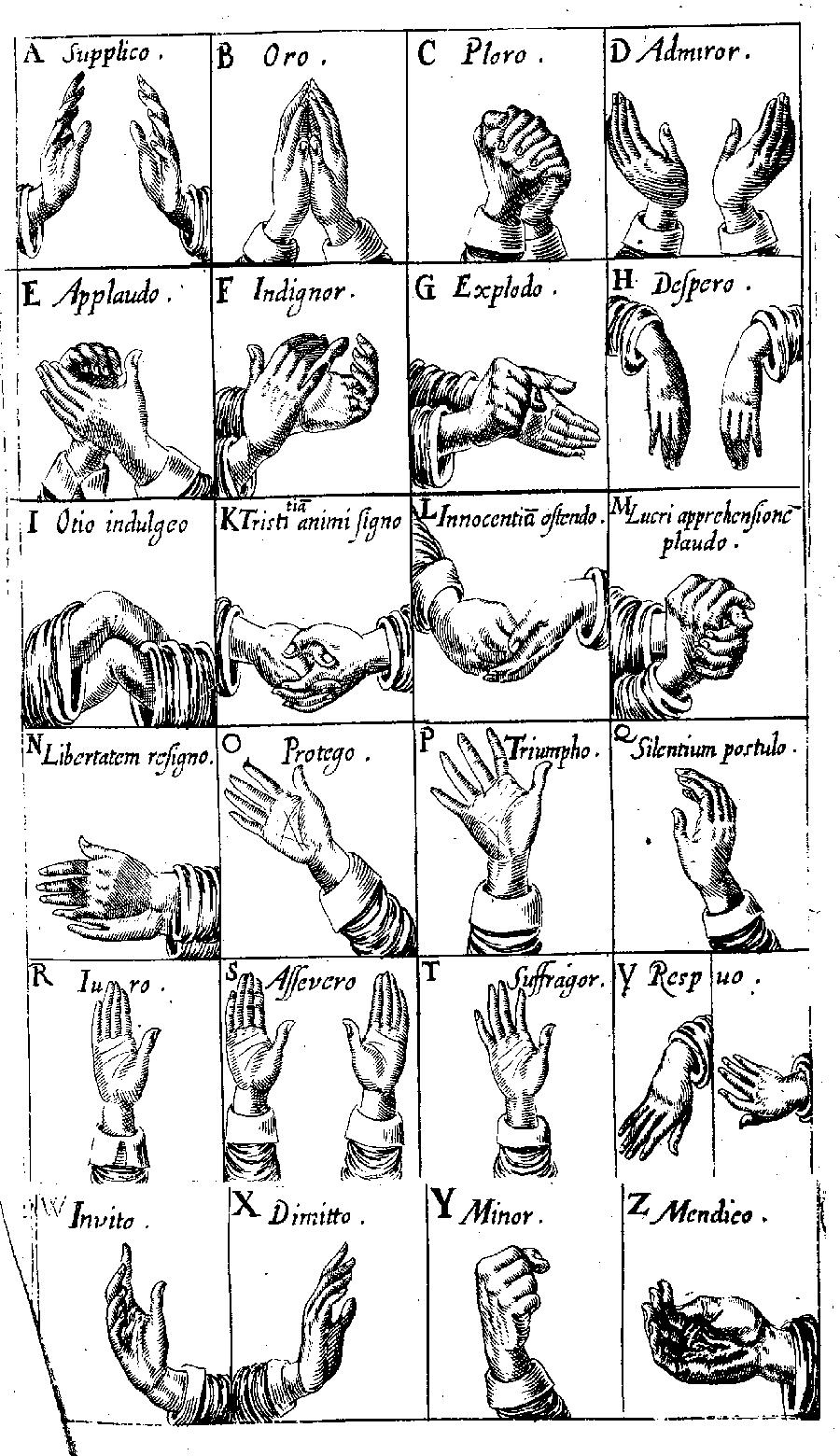

The title page of Bonet’s work features an allegorical image that I like quite a bit: a lock binding a man’s mouth, labelled ‘nature,’ being picked by a hand labelled ‘art.’ Some sample images from the same book: